On March 25, the feather from a living California condor fluttered down through the frosty redwood air to reach the ancestral ground of the Yurok Tribe for the first time in more than a century.

A primary flight feather about ready to molt off, it had been plucked by the powerful beak of a red-headed, adult condor from his wing while preening himself on an aviary perch of cross-hatched logs overlooking a vast treetop canopy of gigantic redwoods. Another feather soon dropped. The condor, or prey-go-neesh in the Yurok language, arrived at this new setting in Redwood National Park the previous day to fulfill a mission of incredible responsibility. On massive outstretched wings, spanning about 9.5 feet, he displayed a black tag—color coding indicating his unique number of 746 in a centralized database tracking condor lineage called the studbook. Inside a newly constructed flight pen, he loomed over his only company, a stillborn calf carcass from an organic dairy.

But in three days, he’d be temporarily joined by a cohort of four juvenile condors, all hatched in captivity and unexposed to the slipstream of free air. Condor 746’s job was to mentor the young condors so they’d be better prepared for their fast-approaching, historic release into the wild.

The entire population of California condors was down to 22 in 1982, and none of them flew free in the wild. Since then, though, the California Condor Recovery Program (CCRP), overseen by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS), has led the repopulation of condors through the successful collaboration among dozens of organizations, including zoos, NGOs, international partners, and local, state, and federal agencies. The condor population has gradually grown to 537, as of the last official count in December 2021. Of them, 334 are free-flying.

As the population expands, the biologists add new release sites, and slowly the giant birds have expanded from Southern California to Central California, Arizona, and Baja California. The historical condor range had stretched as far north as British Columbia, and once included the Klamath Basin and all the ancestral and modern-day lands of the Yurok. In 2003, tribal elders leading an effort to identify cultural and natural resource restoration needs determined that the condor was the most important land-based animal to return to Yurok lands.

To make a reintroduction work, the Yuroks and their partners spent years studying condors and their needs. They evaluated DDT and lead environmental contaminants, finding that bullet fragments containing lead in animal carcasses pose a continuing and deadly threat to condors. They studied sites to identify the best place for a new release facility, one with the right habitat, food availability, and roosting and breeding locations. A search by the Yuroks, USFWS, and Ventana Wildlife Society identified a prime site in Redwood National Park, and this resulted in an alliance between the Yuroks, National Park Service, and California State Parks to manage it.

The park is home to various endangered species, so the team studied whether reintroducing condors would jeopardize the survival of the others. In March 2021, the CCRP gave the all clear for the establishment of the Yurok condor release facility, and with it the promise of a renewed connection to the land and tradition.

“With our families, our lives, our environment, our river, our streams, our fish, our wildlife, we pray for balance, not just for us, but for the world,” says Yurok Tribal Council Chairman Joseph James, who grew up in a village on the lower Klamath and sings his own song honoring condors. The Yuroks consider themselves a world renewal people, meaning they believe a foundational reason for their being is to keep the world in balance and renewed. And in their sacred jump dance, they use fallen condor feathers to show their respect for the birds.

“As we dance and pray, that bird, he or she, is flying up in the sky carrying those prayers for us,” James says. “They’re a scavenger bird, playing their part here on Earth.”

Yurok Tribe Wildlife Program Director Tiana Williams-Claussen, a biologist and tribal member who helped start the Yuroks’ condor program, first worked with condors with the Ventana Wildlife Society in 2009. As part of her training she released a condor by hand into the Big Sur countryside. Admiration turned into passion as she became a protector of the condor story.

Condors have no voicebox like other birds do. The sounds they make are more like reptilian hisses and grunts. However, in an interview in April, Williams-Claussen told me that this did not stop Condor from having a song—a prayer. When asked by Creator to come up with the world renewal song, the most important of them all, Condor was reluctant because he could not sing like the other birds. But he was convinced to try. He hissed and grunted.

“But Creator saw his spirit, which we consider to be a particularly kindhearted spirit—the spirit of renewal,” Williams-Claussen says. “‘That was beautiful. Let me sing it back to you.’ And sure enough, Creator sang it back to Condor. And it was the most beautiful and powerful song that has ever been sung. It was that spirit that was conveyed, and that is the song we continue to sing today.”

In September 2020, wildfires forced the evacuation of 44 condors from the Oregon Zoo’s breeding facility at the Jonsson Center for Wildlife Conservation in rural Clackamas County. Twenty-six of the birds ended up at The Peregrine Fund’s World Center for Birds of Prey (WCBP) in Boise, Idaho.

Three of these refugees, a female and two males eventually assigned the numbers A0, A1, and A3, would become the birds planned for release by the Yurok. In a pre-release pen with 16 other juveniles and one adult mentor, they met one more young male condor, A2, to round out a quartet to start the repopulation of the North Coast.

Before they could fly, the juvenile condors needed to learn social skills and how to eat in a group, says Leah Esquivel, the Peregrine Fund’s propagation manager. Socialization with other condors has proved vital to the condor recovery, and so has deciphering their ancestry.

Condors are selected for breeding and for eventual release mostly because of family lineage. It’s a fluid process. Deaths by lead poisoning, wildfire, and other causes can quickly shift what is an over- or under-represented line.

From the genetic bottleneck of 22 condors, DNA fingerprinting revealed 14 distinct lines from what would be called the founder condors. Later more advanced genomic testing revised the number of founders down to 13. However, this is still a high degree of genetic diversity considering that condors almost went extinct.

In an effort to better understand the genetic diversity of the species over a wider historical range, Jesse D’Elia from USFWS analyzed tissue samples from 93 condors housed in museums across the world. The condors had been collected from Clark County, Washington, down to Baja, Mexico, between 1825 and 1984. The California Academy of Sciences had 14 condors that ranged from San Diego to Fresno. D’Elia analyzed four condors from the Pacific Northwest, which included a condor from Humboldt—near to the Yurok release site.

The study showed that the genetic sequence D’Elia examined in the Pacific Northwest condors was also present throughout the entire range of condors, meaning the northern condors were not genetically isolated but intermixed over the historical population.

Katherine Ralls, an emeritus biologist with the Smithsonian, has been a genetics advisor to the CCRP since the time when no condors lived in the wild. She and her colleagues have precisely determined the genetic lineages, or kinship, for the condors and use this information to best ensure genetic diversity for all condor captive breeding. Ralls says paying attention to the genetics minimizes the chances of inbreeding. Improving genetic diversity strengthens a species’ ability to survive catastrophes, such as disease, and to adapt to shifting environmental conditions resulting from climate change.

The condors with genetics that most maximize the genetic diversity of the entire condor population are the top release candidates. They get matched to optimal release sites. Since females have a higher mortality rate in the wild than males, a bird’s sex also plays an important role in release placement.

Releasing captive born condors into the wild has always been inherently risky. Just living in the wild was enough to nearly cause the species to go extinct. But on top of this, the Yurok release site hadn’t seen a condor fly overhead in a century. Unlike other release sites, the first four Yurok condors would be going it alone.

The four young condors traveled from Boise to the next stage in their reintroduction journey. In September 2021, the Yurok condors and five others from WCBP’s pre-release pen crowded in with another juvenile in a release pen operated by the Ventana Wildlife Society in San Simeon.

Ventana’s San Simeon pen in Central California is centered within a free-flying condor flock. Every day the Yurok condors watched wild condors feed on carcasses left outside the pen by biologists. For the captive juveniles, this was their first time seeing condors in the wild. They watched them fly around, land, eat, interact with one another, and then fly away. There wasn’t an adult mentor bird in the pen because so many adults were outside. But last fall, the Yurok condors saw their pen pals get released, one by one, to join the free-flyers. All the insiders could do was observe and learn.

On March 28, 2022, after a six-month stay, Ventana transferred the remaining condors from San Simeon north to the Yurok pen. Staff from the Oakland Zoo did checkups on the condors, including taking baseline blood samples. Ventana and Yurok biologists carried each condor in a large pet carrier with covered-over windows. Humans must be kept from sight as much as possible. Becoming accustomed to humans puts condors in grave danger, because it draws them closer to potential fatal hazards they would not ordinarily face in nature. When this happens, condors must be recaptured for their own safety. They then can become unreleasable. But now, eye contact was inescapable.

Their wing tags were renumbered and the radio and cellular/GPS location tracking transmitters were attached. Once released, these transmitters would be lifelines between them and the biologists.

Without the wild adults around, it was now time for 746 to begin his mentor duties. The 8-year-old had never been paired up for breeding since his genetic line wasn’t a priority. Condors have a very strong hierarchical social system and set of behaviors. So because 746 was unattached and very dominant while previously on exhibit at the Oregon Zoo and WCBP, he had been picked to help pass on the condor code.

A0 was introduced into the pen first, followed by A1. Each flew up to the perch, displayed its spread wings, and snapped back and forth with the mentor. Not long after getting the lay of the land, they ate from a meat buffet—five different animal carcasses. They did not seem distressed or upset. They appeared inquisitive, their heads swiveling around, eyeing every part inside the pen and outside.

The mentor didn’t have the only eyes on the young condors. Around the clock and adjacent to the flight pen biologists monitored the condors from behind one-way mirrors, cut into two metal shipping containers that serve as wildfire-resistant observation rooms. The biologists weighed the condors every time one landed on a small log affixed to a scale.

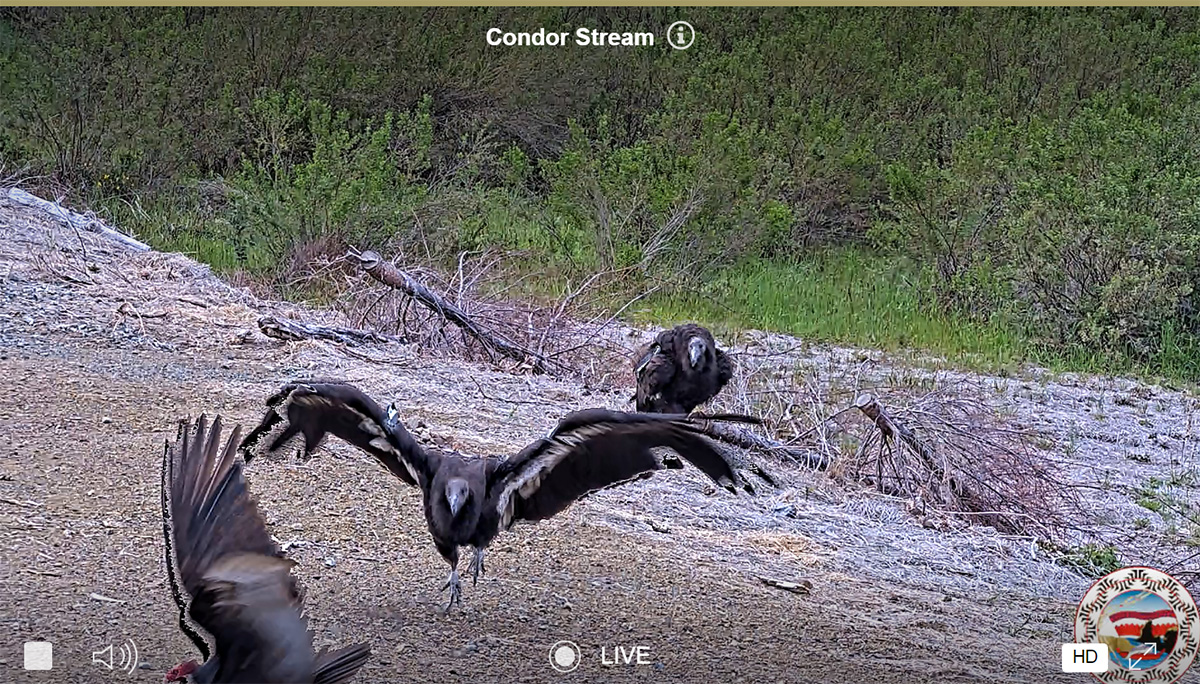

A live video feed captured turkey vultures buzzing by the pen as A2 and A3 were added. Turkey vultures were a great sign. The young condors would learn from their close but smaller relatives.

As the juveniles shifted around and explored their new temporary home, one thing stayed constant. Whenever the mentor condor was ready to head to his favorite spot on the crosshatch perch, the end of a top log closest to the best view of the redwood expanse, he hardheartedly exercised his claim by nipping and flushing off any squatter. Lesson one: that’s my spot. Training had begun.

Over the weeks leading up to the first release, the biologists closely monitored the condors. They watched how the condors behaved with one another and how they reacted to the stimuli outside of the pen. The birds became more familiar with the turkey vultures and ravens during regular visits for food. The time in the pen also allowed the condors to strengthen their bonds with each other. They imprinted on the pen and the countryside they could see stretching on for miles around it.

Condors also had to become comfortable going in and out of a double door trap at the end of the pen. The trap allowed the biologists to release and recapture the birds for visitations, biannual checkups, and emergencies.

Chris West, a senior wildlife biologist with the Yurok Tribe who manages the condor program, says the young condors ate well and maintained healthy weights. They acted like well-adjusted condors—sometimes affectionate, sometimes playful, sometimes a pain in the mentor’s tail feathers. More and more their personalities showed. The males tended to form a pack. The female preferred to be off to herself. And the mentor continued to defend against interlopers attempting to perch on his spot.

To provide the public with more information, operation of the Stone Lagoon Visitor Center just south of Redwood National Park transferred to the Yuroks in April 2022.

“We’ll have live streaming of the condors when they are at the release facility. And we’ll also have interpretation panels dedicated to the reintroduction of condor to the area,” says Yurok tribal member and interpretation coordinator Nicole Peters. “It’s a center where people can come to learn about Yurok history and culture from Yurok people.”

On May 3, 2022, turkey vultures and ravens flew over the tall electrified fence that encircled the condor compound and protected the pen and open ground inside from predators, like bears and big cats. In this safe zone, the common wild-flying birds fed from a freshly deposited carcass. For weeks, the juvenile condors watched their cousins ravage scraps left to entice them next to the pen. Now, inside the double door trap, A2 and A3 waited separately from the others. From an observation room, Williams-Claussen moved levers that engaged the pulley system to remotely open the outer trap doors.

A2 and A3 had never before seen this unobstructed view of nature. Over their lives, the only world they could touch had been contained within fixed boundaries, a minuscule fraction of the distance a wild condor could fly in a single day. Now A2 and A3 were unbounded.

A little more than a month after the younglings joined the Yuroks, the release began. The biologists chose to stagger the timing to ensure the best chance of successful introduction into the wild. Since there were no other free-flying condors around, the biologists didn’t want to send any of the juveniles solo into the wild. Yet leaving the mentor and two others behind motivated the first two released condors to keep returning to the pen. Carcasses would continue to be placed outside the pen for further motivation.

The biologists chose two males for the first release partly because the males were closer with one another than they were with the female, making them good travel buddies.

A2 and A3 had both stepped away from the new openings. They quizzically bobbed their heads, eyeing the scenery anew. After minutes passed, A3 made tentative and fidgety steps closer, leaped onto the perch at the edge of the top opening, and flew like a rocket out of the compound and into the sky above the forest. He had skipped right over the meat the biologist had carefully prepared for the release. Seconds later, A2 shot from the perch to join his airborne wingman.

The first free-flying condors above the Pacific Northwest—above the Yuroks’ sacred land—in over a century. They soared above redwoods where their ancestors once roosted and nested. A2 returned four hours later to feed on the carcasses, but A3 headed off on his own.

After the release the two condors received Yurok names. Williams-Claussen gives their meaning: “Poy’-we-son translates to ‘The one who goes ahead,’ but also harkens back to the traditional name for a headman of a village, who helps lead and guide the village in a good way. A3 is one of the more dominant birds, and I expect that he’ll be a leader among this flock and for new birds coming in.”

“Nes-kwe-chokw’, which translates to ‘He returns’ or ‘He arrives’ and is representative of the historic moment we just underwent, as condors return, free-flying, to the Yurok and surrounding landscape.” She adds, “He is a confident bird, often jockeying with A3 in play, but also to help establish his place in the hierarchy.”

In the days that followed, both condors stayed true to their Yurok names, as their different behavior reflected their individual personalities. Nes-kew-chokw’—A2—hasn’t strayed far from the pen, sleeps in a favorite snag in a close-by tree, and regularly interacts with A0, A1, and 746.

However, once out of the flight pen, Poy’-we-son—A3—didn’t return until two weeks later. While away, he had faced a nasty snowstorm that grounded him in a blown-over tree. Once the weather cleared, it took him days to finally find the pen. Before returning, he had flown a little over 10 miles away from the pen, and his longest movements in a day covered about 10 miles.

“He’s been doing really well at navigating the terrain,” says West, the head biologist for the condor program, who has been tracking A3 in the field. “As far as learning the ins and outs of flight, hopefully he’s going to have a lot to teach A2 at this point if they go and take some trips together. A2 understands how to be a homebody and get fat. He can share that with A3.”

Indeed, A3 did pack on a few pounds as he settled in and demonstrated comfort coming and going from the release site. So, on May 25, the Yurok team released the lone female A0 while A2 waited outside. At the time, A3 was again out and about. But like A2 before, she flew from the pen right away, returned soon afterward, and preferred to stay nearby.

A0 was named Ney-gem’ ‘Ne-chween-kah, and Williams-Claussen explains, “It means, ‘She carries our prayers.’ There’s a lot of thought and a lot of heart that goes with that name. We say that Prey-go-neesh carries our beliefs, our energy, our prayers when we’re asking for the world to be in balance. In our traditional stories, Prey-go-neesh is referenced as a man, and I can’t speak one way or another as to whether our females will play that role, or have their own equally important one. But from my perspective, as a Yurok woman and a mother, as our only female in this first cohort, she represents the creative life-force energy that females bring to the world.”

Since A0’s release, all three of the free Yurok condors have returned together to visit the pen and see both A1 and their mentor 746. Once A1’s faulty GPS transmitter is replaced in June, the biologists aim to release him when other free condors are present.

Before becoming a mentor condor, 746 had been named Paaytoqin, meaning “come back” in the language of the Nez Percé, the Indigenous people of Boise, where he grew up in the World Center for Birds of Prey condor pen. Paaytoqin had earned the name because he had returned to WCBP after serving at the Oregon Zoo. His name now takes on new significance. Aside from mentoring the young condors, he has become a magnet that will continue to attract the released condors to the pen and keep them coming back.

The next cohort of condors, two males from the Oregon Zoo and a male and female from WCPB, is scheduled to be released in August. Paaytoqin will be waiting to show them the way. The Yuroks plan to release four to six more condors every following fall for 20 years, by which time the Pacific Northwest flock will hopefully have reached between 80 and 120 condor releases and more than a decade’s worth of wild hatchlings.

The Flock Grows

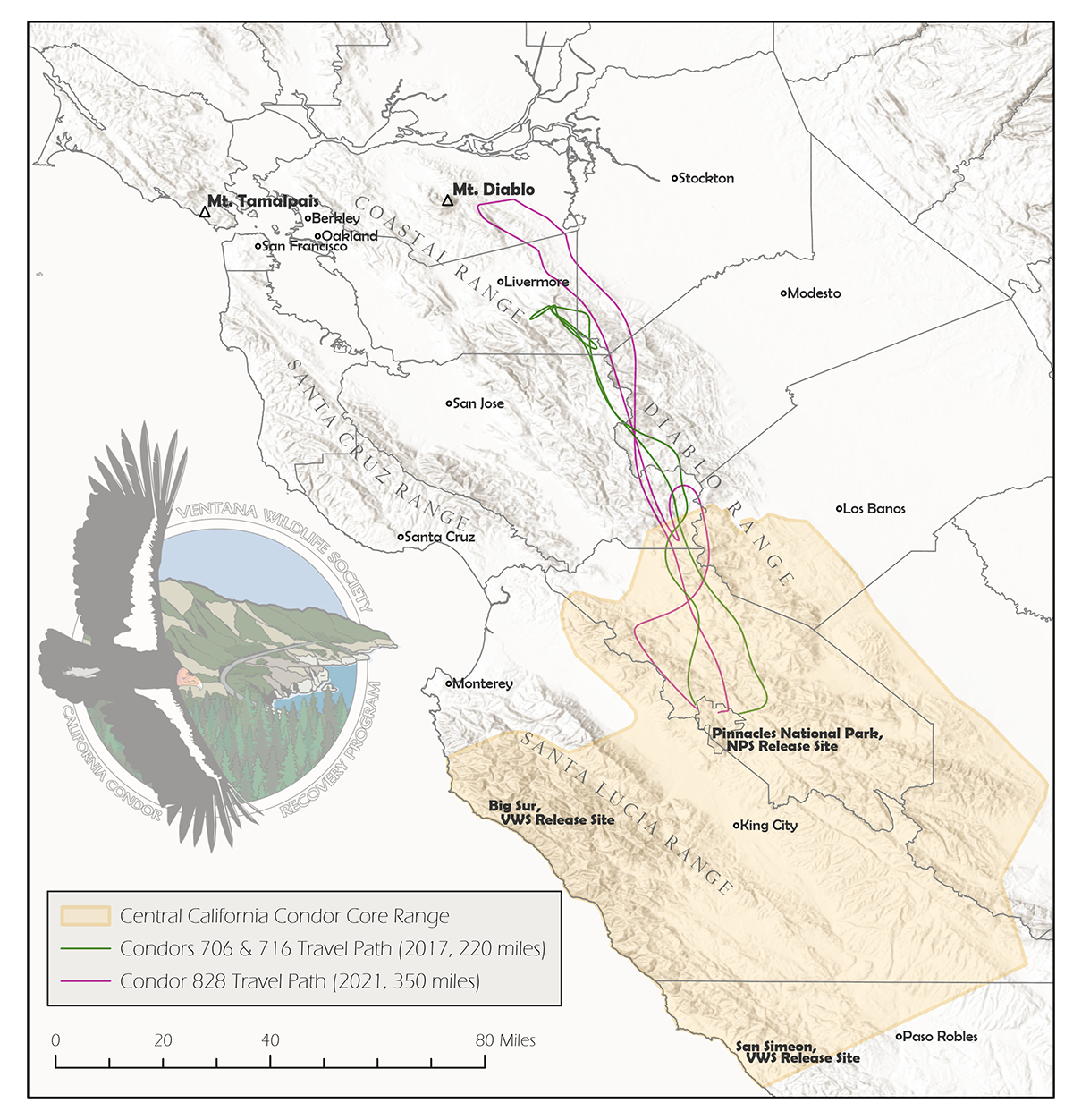

As the Pacific Northwest flock grows and its range expands, so does the likelihood of it encountering the wild Central California flocks. The Bay Area is roughly the midpoint between them. They could overlap along the Diablo Range southeast of the Bay or around Mount Tamalpais to the north of it. As the crow flies, Redwood National Park is about 250 miles from Mount Tamalpais. And as the condor flies, this is a little over a day trip.

Mixing of flocks regularly occurs within the three Central California flocks in Big Sur, Pinnacles, and San Simeon, which are much closer together. However, for years condors from Central California flocks and Southern California flocks have been mixing. Most of this happens with subadults that haven’t yet reached sexual maturity or started to pair up. Some of the condors that made trips up or down the coast opted to even switch flocks.

In 2017, Big Sur condors Icarus (706) and Orville (716) flew to within 7 miles of downtown Livermore. Last September, condor 828 flew to the edge of Mt. Diablo. Both visits to the Bay Area likely included other condors that weren’t fitted with GPS tracking, since condors often travel in groups, says Ventana Wildlife Society head condor biologist Joe Burnett.

So it’s possible that one day Yurok condors will interact with condors they met while penned in San Simeon. As long as the Pacific Northwest and Central California flocks continue to grow, it’s not a question of if mixing will happen. Just a question of how soon.

For now, in far Northern California, it’s been more than 100 years since a Yurok has seen a condor flying in the sky over their land. Soon, no Yurok will know a sky without condors.

“To be able to hold two condor feathers, naturally dropped, here in the Yurok homeland, it was a special moment—a proud moment—knowing that our birds are home now,” says James, the Yurok chairman. “They get to shed their feathers just like any other bird here. Now they will be dropping feathers throughout their whole lifespan.”